By Scott Pritchett

THE CAMPAIGN

In September 1944, Finland secured a separate peace with Russia,

which resulted in an operational dilemma for the Germans that cast the

fate of the soldiers of Heeresgruppe Kurland. Despite the agreement with

Russia, Finland and Germany coordinated a period of time - until 15

September - to withdraw German forces from Finland. In fact, neither

could have afforded not to do so. On the one hand, Germany would never

have agreed to surrender her forces in Finland to the Soviets and, were

Finland not to agree to the unobstructed withdrawal, the Germans

certainly would have fought the Finns to extricate herself. In any case,

scarcely enough time was available under the provisions of the agreement

and the extent of the withdrawal became a heated debate in the German

high command. Germany still required Baltic ports, not only to evacuate

her forces from Finland, but also to secure continued shipments of

war-critical ore from Sweden. Baltic ports would also keep the Soviet

fleet in check and bottled up in Russian waters. The German’s strategic

position so far north also kept the Soviets from forward basing the Red

Air Force to strike deep in to Germany. Finally, they allowed the

Wehrmacht units fighting on the northern most portions of the eastern

front to continue being supplied and having the means to evacuate its

wounded and the mounting numbers of ethnic German refugees.

The establishment of the Kurland Bridgehead and the reasons the Germans

decided to fight to hold on to it had their roots as far back as the

beginning of the year 1944.

Additionally, to understand the relative positions of opposing forces in

the Courland bridgehead by mid-September 1944, the campaigns fought

earlier that year need to be generally understood. Two events that had

the most impact were first, the successful Soviet offensive in January

and February 1944 - which broke the 900 day siege of Leningrad allowing

the Red Army to concentrate it’s Fronts in the north - and second, the

successful offensive against Heeresgruppe Mitte later that summer

(Operation Bagration) – that defeated the German center. In this latter

campaign the northern wing of the Soviet offensive used the forces that

had concentrated following the Red Army’s relief of Leningrad. It was in

the final stages of this summer offensive, specifically during July

1944, that the Red Army decisively defeated the 3. Panzer Armee, pushing

it west and creating a huge gap between it and the 18. Armee to its

north. As Heeresgruppe Mitte collapsed, the Soviets, recognizing their

success and the opportunity at hand, pressed their attack west.

Heeresgruppe Nord (later Heeresgruppe Kurland) on the left flank of

Heeresgruppe Mitte, was forced to either abandon the northern portions

of the Eastern Front and move southwest in to Prussia or withdraw north

in to the Courland area. Because of reasons already noted concerning the

importance of this northern area, Generaloberst Schörner withdrew and

concentrated his army group into the Courland area and, by August, found

his army group more and more isolated by the advancing Russians.

The campaign is generally broken in to in six battles. These battles were defined by major Soviet offensives, however the overall fighting from 15 September 1944 to 8 May 1945 seldom if ever paused. The dates of these battles are generally designated as follows:

- First Battle 26 Oct-7 Nov 1944

- Second Battle 20 Nov-30 Nov 1944

- Third Battle 22 Dec- 31 Dec 1944

- Fourth Battle 24 Jan-5 Feb 1945

- Fifth Battle 20 Feb-15 Mar1945

- Sixth Battle 18 Mar-31 Mar 1945

The fighting in Courland from the German perspective was defensive. However, several large attacks were made to regain contact with forces in East Prussia and to push the main line of resistance east from Libau - the key and critical port for the bridgehead. All branches of the Wehrmacht: the Heer, the Waffen SS, the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe took part in the campaign, making the award of the KURLAND band unique for such a decoration. There was little variance in either the method of attack, the locations of focal points for each attack, or the conduct and outcome of the six battles. The objective of the Soviets was to split the two subordinate armies of Heeresgruppe Kurland and drive to the coast in order to capture the port of Libau, thus cutting off the German support base and setting up the conditions for defeating the army group in detail. The Red Army's attacks were somewhat unimaginative, opening in almost all cases with the customary heavy artillery barrage. However, early in the campaign, during the opening of the second attack the Soviets initially postponed the artillery barrage and mounted a massive aerial attack of sustained duration. In this, as in all previous and subsequent attacks, the Germans were able to hold on through the opening phases and follow up with counterattacks that ground the Soviets to a halt. The typical focal points occurred frequently in the center (east and southeast) of the bridgehead. The main efforts most often occurred either between Autz and Doblen, in the vicinity of the city of Frauenburg or at the seam between the two armies of the army group. All German units experienced harsh conditions and tough fighting, but several divisions repeatedly bore the brunt of attacks. The 4., 12. and 14. Panzer Divisionen and the 205. and 215. Infanterie Divisionen in particular saw some of the heaviest fighting. As on all parts of the Eastern Front, the Panzer Divisionen were the fire brigades that sealed of the Red Army penetrations while the Infanterie Divisionen held the shoulders and attempted to stem the tide. In this campaign the pilots and crews of the Luftwaffe's Jagdgeschwader 54 remained constantly engaged, suffering casualties along side their ground comrades of the Heer and Waffen SS.

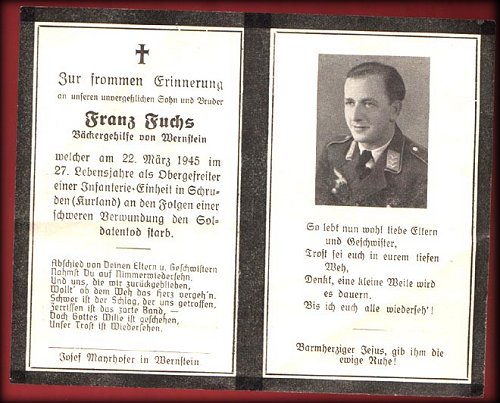

Death notice of Luftwaffe man Franz Fuchs who died in defense of the Courland bridgehead on 22 March 1945, the sixth and last battle of Courland - Courtesy Richard van Atta collection.

Likewise, the ships of the Kriegsmarine played invaluable roles with fire support, supply and evacuation. The German's skill at defeating the Soviet attacks was usually complimented by the high rate of casualties they inflicted on the Russians. The fifth offensive by the Russians was to have delivered the final blow, but as in the previous four attempts, it failed to split the army group. The Soviets were never fully able to regenerate the fury of earlier attacks after this. The Germans, if never able to match the numbers of men and material the Soviets could bring to bear, clearly broke their spirit by the middle of March 1945. Hereafter, while attacks continued, the final offensive was not executed with the intensity of earlier attacks. On 18 March, Größadmiral Dönitz presented his plans at the Wolfschanze for the withdrawal of the army group with the assistance of the Kriegsmarine. He estimated it would take 9 days to withdraw. However, the plan - Operation Laura - was denied, sealing the fate of Heeresgruppe Kurland.

Courland appears to have been an obsession with the Soviets. Although the Red Army could and did replace spent units with complete fresh formations, the Red Army had battered itself well beyond the point of diminishing returns considering the overall course the war was taking. Everywhere they were routing the Germans, yet Courland stood. The fighting became very limited in scale after the sixth battle. Perhaps the imminent fall of Berlin had a direct impact on their resolve to press the fight further. On 3 May, the Soviets lit up the Courland pocket with every available gun and the Germans steeled themselves for yet one more assault, but to no effect. The Soviet display merely marked their exhilaration over the fall of Berlin. Heeresgruppe Kurland thus began to prepare for its seventh battle of Courland by thinning its forces in less threatening sectors and reinforcing those areas likely to have to take on the brunt of the next assault. It was a battle that would never be fought. Unable to defeat the Germans, and with the complete collapse of Germany imminent, the Soviets had withdrawn the bulk of their offensive army. Heeresgruppe Kurland issued its final orders on the night of 7/8 May 1945, informing units that a ceasefire would ensue beginning at 1400 on 8 May. The fighting in Kurland officially ended 8 May 1945 and roughly 270,000 members of the German Wehrmacht marched east in to Soviet captivity.

The northern armies of Herresgruppe Kurland, 16. and 18. Armeen, remained undefeated right up until 8 May 1945, with sporadic fighting continuing for the next couple weeks. Their eight-month resistance allowed for the evacuation of 2.5 million eastern Germans and the evacuation of numerous German units used to defend the heart of Germany. The efforts of these tough Wehrmacht soldiers also saved an estimated 3.5 million German soldiers from certain and needles captivity at the hands of the Soviets. As it was, Heeresgruppe Kurland's own reward for the determined stand it made was in fact the same fate from which it saved millions of others. With the exception of a portion of the battered divisions that had been withdrawn over the course of the campaign or were able to get out of the bridgehead in the final days, the Wehrmacht soldiers of Heeresgruppe Kurland marched east in to Soviet captivity early in May 1945. Save for the likes of SS-Unterscharfuhrer Riekstins who fought on for another fourteen years, and those few lucky enough to survive years of harsh captivity at the hands of the Communists, many were never heard of again.

![]()

© Copyright Wehrmacht-Awards.com LLC |