by COL Scott Pritchett

METZ 1944

The Metz 1944 cuffband is easily amongst the most obscure battle honors of the German Wehrmacht in World War II. There are a number of reasons for this. First, the cuffband developed in the last six months of the war and at a point of time where the battle for Metz was overshadowed by more significant battles. Secondly, the number of Wehrmacht members who were eligible for the award was very small. Additionally, from a collecting standpoint, authentic examples are excessively rare and so, seldom come up on the collector network for informed discussion. Lastly, there is a general lack of published history about the events that resulted in its institution as a battle decoration of the Wehrmacht. While author Anthony Kemp published a book in 1981 entitled The Unknown Battle Metz, 1944 - which was almost unique in its effort to bring to light the fight between the American XX Corps and an odd assortment of German units that opposed one another between September and November 1944 – the work has had little follow up by other historians and only briefly mentions the cuffband. In fact, only Kemp himself has updated his own work in the recent writing published through Heimdal entitled Metz 1944, One More River to Cross. These two works largely represent the extent of information readily available to collectors today about the battle. There is scant information that has come to light beyond the official institution order and some veteran accounts. The result is that over twenty years later, Kemp’s initial characterization of Metz as an unknown battle remains an appropriate characterization of the Wehrmacht’s battle honor, the Metz 1944 cuffband, as well.

THE BATTLE

Part 1: HISTORICAL MILITARY POINTS ABOUT METZ

Metz is a city with a long history of fortification. Deriving its modern name from the Latin word “Mediomatrica “, it was named by the Romans, who first fortified it due to its importance as a military outpost and crossroads for its legions. Metz has been associated with warfare ever since. It is known to have been successfully taken by the Huns in the 6th Century, which was probably the only successful conquest up until its capture by the Americans in November-December of 1944.

Metz is situated between two rivers, the Moselle and the Sielle. This geographical fact saw it grow quickly in importance as a hub and crossing point for commercial and military traffic. Initially a city in its own right, for more than 1500 years Metz was continuously rebuilt, expanded and improved as a fortified area, so much so that its identity as a city faded and yielded to a formidable reputation as a fortress. Sometimes ahead of developments in warfare and sometimes behind them…but almost always under French or German ownership…the history of Metz’s fortification was a reflection of current military thoughts on defense throughout its expansion. Technological advancements such as artillery, high explosives and electronic communications all impacted the nature and structure of Metz’s fortifications, gradually expanding them in size and sophistication. Improvements in the mobility and logistics systems went hand in hand toward the ability of armies to sustain the conduct of campaigns. As a result, Metz transformed from the role of fortifying for the sake of its own preservation, to one of fortifying an area in order to deny terrain essential for the passage of armies. At the height of this latter role, around the beginning of WW I, a fully equipped Metz garrison was estimated to properly require and army of 250,000 men to capture it. The Imperial German General Staff considered its possession to be the equivalent of 120,000 men. The French would have certainly tested these theories had not the Armistice rendered such an undertaking unnecessary.

By the early summer 1944, the Wehrmacht had shown little inclination or forethought toward using it on such a grand scale. In fact, after the fall of France in 1940, Metz was stripped of many of its guns and equipment. It was allowed to atrophy in many respects, such as maintenance of communications systems. Metz itself was garrisoned as a “college town” of sorts, having both Heer and Waffen SS schools located within its environs. These facts notwithstanding, Metz was still a formidable maze of forts, observation posts, connecting entrenchments and tunnels that could quickly be obstacled to provide a would-be defender with a robust position. With the Allies’ breakout from the Normandy beachhead and the introduction of an Allied army in the south of France that threatened the Saar region of Germany, Metz once again became a focal point.

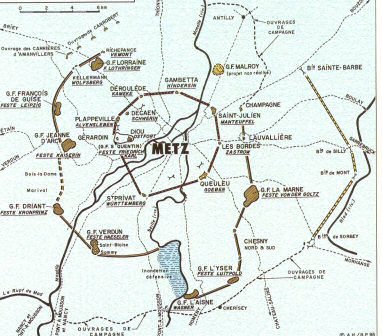

Illustration 1; Schematic showing the main forts that comprised the immediate defenses of Metz. The stubborn – if ad hoc – German defense would require the US Army to take each one. Several forts held out for a couple of weeks after the battle had been declared over (Heimdal Publications).

In simple terms, the city sits on one or more large islands in a bowl between

the two rivers, each that runs generally north-south. Its defenses extend

for miles around the inner city. To the north, the terrain is steeply

hilly and compartmentalized – not at all suited for armor, and is the most

direct approach past the fortified area. Consequently, the Germans

organized their strongest defenses on the high ground to the west and northwest

of the rivers. The terrain of the southern approaches are, likewise, not suited

for armor, and tend to canalize a would-be attacker into a southwest to

northeast approach. Metz’s weakness, if it could be said to have any, were

to the east. Assuming a force could get across the rivers Moselle and

Sielle by crossing either north or south, a reduction of the forts would have

the highest probability of success if attacked from the east, back along the

line of approach. The forts that comprise the Metz complex present a

dizzying array of names and types. To add to the complexity, the main

occupiers throughout history, the French and Germans, each assigned different

names to the various groupings. Fixed artillery types also varied, being

comprised variously of 100 mm, 150 mm and 210 mm to name the most prominent.

By 1944, much of this artillery had been stripped and sent to places like the

Atlantic Wall and that which remained was in need of repair – many pieces were

without gun sights for example. In spite of such challenges, extensive

written plans of the forts existed and in a few brief weeks, through

improvisation and energy, the Germans were able to get much of what remained in

to some kind of working order. Eventually, these same plans would greatly

assist the Americans in reducing Metz, fort by fort.

Built to withstand the heaviest of siege artillery and positioned on terrain

highly unfavorable to armored forces, Metz was, nevertheless a battleground for

infantry, as the events of late 1944 were to again show.

Illustration 2. Aerial view of one of Metz’s many formidable forts. Note the restrictive terrain that approaches the fort from all sides, making the use of armor difficult. In the end, the Americans had to use close quarters combat and repeated assaults to capture each one (Heimdal Publications).

Part 2: BACKGROUND TO THE BATTLE

For the hard-fought attackers and defenders in the Battle of Metz, it is

unfortunate that their stories have remained largely overshadowed by two other

great battles that punctuated the beginning and end of the capture of the

fortress city. Were it not for Operation Market Garden in September 1944

and the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, the battle for Metz, from

September through November 1944, would certainly have taken on greater

notoriety. Therefore, it is important to digress for a moment and arrange

the Metz sector into the wider perspective of operations across the Western

Front in order to understand why it was accorded less importance.

The extent of the collapse of the German front following the breakout from the

Normandy beachhead in July 1944 caught the Allies by surprise. It was a

catastrophic defeat for the Wehrmacht, and masses of troops were killed or

captured. The materiel losses were on an even more massive scale.

Prior to the invasion of Europe, the post-breakout planning had foreseen a more

cohesive German front behind the Normandy peninsula and had envisioned that the

Allies would need to pause on the Seine River in the face of such an effort, in

order to build up logistics for the advance into Germany. This was not

just a purely “supply” calculation of the “troops-to-task” requirements, but an

operational calculation that recognized an attack into the heartland of the

Reich could not be accomplished solely over the beachhead, but would require the

capture of actual ports. Post invasion planning did not anticipate or

rapidly adjust for the contingencies that developed. German resistance had

successfully denied the Allies capture of sufficient key port facilities.

Cherbourg was not lost to the Americans and functioning on their behalf until

early August 1944. But Brest, Dieppe, Dunkirk and Antwerp were still in

German hands by the end of August 1944. Antwerp in particular was long

seen as the key port for sustaining the drive in to Germany.

However, with the overwhelming success of the breakout, the Allies found

themselves rushing headlong east toward the frontier of Germany. The pace

of events put them about a month ahead of D-Day calculations in terms of time

and distance, but not logistics or troop strength. Additionally, the

wholesale destruction of the rail network in France by the Allied air forces,

that so successfully hampered the Germans’ reinforcements during the Normandy

campaign, now caused sustainment problems for the Allies as they pushed across

France. The result was an over dependence on trucks to haul supplies over

lengthening lines of communication (the famed “Red Ball Express”). The

Germans however, also severely challenged, were now at least falling back on

their own lines of communication and, in a relative sense, were able to see

things as improving.

By the end of August 1944 while the OKW and its subordinate commander in the

west, Oberbefehlshaber West, Generalfeldmarschall Model hastened to stabilize

the front by reforming both Heeresgruppe B - which contained the majority of

forces in contact with the Allies - and Heeresgruppe G - which was facing the

recent introduction of the Third US Army - the Allies, and the US Third Army in

particular, had come to a halt. The combined result was an operational

pause across the Western Front. Along all sectors, both sides hurried to

gather the means to undertake the battle for the Reich.

At the beginning of September 1944 the Wehrmacht’s command and logistic issues

were huge burdens to effective operations. Because of the complete

collapse of its forces in Normandy and the lack of preparation to the West Wall,

the German high command found themselves short of troops and short of a plan.

Aggravating the circumstances, the Führer filled the void with his own strategy.

In March 1944, Führer Order Number 11 had defined the duties of fortress

commanders. In essence, it required fortress commanders to allow

themselves to become surrounded if necessary, hold terrain to the last man, or

surrender only on approval of the Führer himself. By 3 September 1944,

this order translated in to a strategy of holding everywhere in order to buy

time to strengthen the West Wall. As Patton’s spearheads had reached

Verdun and were pointed directly at the Saar, Metz was designated a Führer

fortress. The German command was forced to comply and went about

organizing a defense.

Illustration 3. General der Infanterie von Knobelsdorf, commanding general of 1. Armee which was responsible for Metz.

The forces positioned for the defense fell under the German 1. Armee. By 1 September it was the strongest German army on the Western Front – a relative statement, as it was drastically short of troops, artillery, tanks and ammunition. What few reinforcements could be made available to this front (at this time Germany had about 700,000 soldiers fighting in the west and about 2.5 million in the east) went to the 1. Armee, as the German High Command was convinced (incorrectly) that the Allies’ main drive in to Germany would come from Patton in the south. Command of 1. Armee was taken over early in September 1944 by General der Infanterie von Knobelsdorf, replacing General von der Chevallerie, who was sent in to retirement. This change occurred as the Allies were resuming their advance. In the face of the recent American successful Lorraine Campaign, von Knobelsdorf could only draw the conclusion the Patton’s Third US Army would continue to drive toward the southwestern frontier of Germany as the Allied main effort. Consequently, he organized his resources to firm up the Moselle River line.

Part 3: THE BATTLE OF METZ 1944

A description of the battle for Metz from the German perspective can be broken

down in to three phases that generally correspond to the three months the battle

was fought – September 1944 through November 1944 (although some sub-forts did

not surrender until early December). It should be noted that the Metz 1944

cuffband was instituted for the defensive success the Germans enjoyed during

only the first phase of the battle. The three phases were:

Phase I: 6 –25 September – Repulse of Third US Army

Phase II: 26 September to 2 November – Tactical Stalemate and Reorganization

Phase III: 3- 22 November – Collapse of the Metz Defense

Illustration 4. “The man can fall but the flag cannot”. Mural from one of several SS training Kasernes in Metz. All armies use similar methods to motivate and inspire its soldiers during training. For the Wehrmacht defending Metz, such motivation had been ingrained over a decade of organizational pride and professional achievement in war (Heimdal Publications).

Phase I:

By 5 September 1944 Oberbefehlshaber West, Generalfeldmarschall von Rundstedt,

in a report estimated that the equivalent of four and a half German divisions

were positioned in the Metz vicinity. These division equivalents spanned the

range of the quality Germany had to draw upon this late in the war. They

included everything from school and garrison troops, to Waffen SS formations,

battle-spent regiments, Volksgrenadier units and Volksturm. Also present were

the usual NSDAP organizations, such as Reichsarbeitsdienst units and party

structure bureaucrats found throughout the Reich. The bulk of the military

forces were arrayed within and to the east of Metz, but units had been

positioned in the key western defenses as both a screening force and a first

line of defense. Most notable of these was the so-called “Officer Candidate

Regiment”, whose combat achievements would largely be responsible for the

institution of the Metz 1944 cuffband. In all about 25,000 troops were in,

around and actively involved in the defensive area of Metz.

On 6 September, American armored cavalry elements of the US XX Corps, making a

renewed, broad-front reconnaissance in the direction of the Moselle for Third US

Army ran in to troops of the 17. Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division, Götz von

Berlichingen, northwest of Metz. This division had been heavily attritted during

the breakout from the Normandy beachhead and was still in the process of

attempting to withdraw to the east side of the River Moselle for refitting. In

fact, the bulk of what remained of the division was already east of the river

and what the Americans ran in to was its rear security. It has often been stated

that the Metz 1944 cuffband came about due to Waffen SS “students” who so

tenaciously defended the city. There was an SS signals school in Metz – whose

members did in fact fight later in the battle – but this belief probably has its

origins as much in the tenacity and skill the rightful Heer claimants to the

cuffband - the Officer Candidate Regiment whose prowess was every bit as

authentic as any Waffen SS unit - as it does in the fact that it was elements of

the Waffen SS from the 17. Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division, Götz von

Berlichingen with whom the Americans first made contact. Thereafter, many

American units that found themselves confronted with a tenacious opponent, would

claim they were up against the SS.

Illustration 5. In the aftermath of a reconnaissance meeting engagement, members of the 111. Panzer Brigade inspect captured M8 armored cars from the US 42nd Cavalry Squadron (Heimdal Publications).

On 18 September, Panzer elements again met US reconnaissance forces in the

vicinity of Lunneville. Making contact with German forces that were “thought not

to be there” rather surprised the Americans, who quickly concentrated their

spread out units. Believing the Germans to be disorganized, several hasty

attacks were mounted in the next few days in order to take advantage of that

belief and thus, seize a bridgehead across the Moselle River. However, the late

summer lull caused by the Allies’ logistics situation had worked to the Germans’

advantage and provided the Wehrmacht time to establish a defense.

During this first phase of the battle, the Americans attempted three attacks to

remove Metz as an obstacle to their advance in to the Reich. All three were

extraordinarily bloody fights, but two were clearly German victories. The third

held only moderate success for the Americans in that it gained a small foothold

across the Moselle, but which could not be immediately exploited.

In the first attack the US 5th Infantry Division (part of the US XX Corps and

the primary antagonist for the majority of the battle) attempted to seize a

bridgehead north of Metz at a town called Dornot. The second attempt came in the

middle – a frontal assault. Both were stiffly resisted by repeated and

successful German counterattacks. In both instances, it was the Officer

Candidate Regiment that bore the heavy work, exhibiting the well-indoctrinated

and proven battle tactic of immediate counterattacks against an enemy who had

gained ground. The third attempt by the Americans was made south of Metz and

succeeded in the small bridgehead across the Moselle, at Arnaville. This attack

found a seam between the III SS Korps and the XLVII Panzer Korps. However, the

nature of the terrain, the tenacity of the German defenders, the heavy

casualties – all compounded by an already constrained allied logistics effort

and half-hearted support for the attack itself by Allied Command – found the

Americans barely holding on and unable to decisively exploit the success.

However, this limited success would eventually contribute significantly to the

capture of Metz.

Phase II:

As September ended, the German command was faced with the choices of abandoning

or holding Metz. It was a foregone conclusion that the next large Allied push

would be to seize crossings across the Rhein River. But the OKW continued to

believe (erroneously) that the main thrust across the river and in to the Reich

would come from Patton’s Third Army. Local German commanders had clearly

determined from the successful repulse of the Dornot bridgehead attempt and

stiff resistance made in other locations that they had now caused the Americans’

XX Corps to temporarily go over to the defense in the vicinity of Metz – halting

the Third US Army, if only temporarily. Naturally, the tenuous bridgehead the

Americans had achieved south of Metz was a concern, but based on these beliefs,

the determination was made that Metz was to continue to be held. Consequently,

the corresponding decision made by General Blaskowitz, Armee Gruppe G, was to

direct General von Knobelsdorf to have 1. Armee reinforce the shoulders around

Metz against the American advance. This was accomplished by stripping forces

from the north to reinforce in the south. Unfortunately, simultaneous with this

reorganization came an overall reduction of the forces available for the defense

of Metz. The OKW needed forces elsewhere as well.

Illustration 6. Two German officers confer in a village somewhere in the vicinity of Metz. While Patton’s Third Army stalled in front of the fortress, other Allied formations continued to push to the east north and south of Patton. German Panzer forces did not show up in great numbers for the Metz battles, however, when they did, they were skillfully employed and frequently decisive to the outcome in the Germans’ favor. This picture also illustrates the condition and experience of the German small unit commanders. Both of these officers are clearly veterans of multiple battles. One is in tropical dress and wears the Iron Cross First Class. The Panzer officer’s face clearly shows the strain of long combat. It was not infrequent by this time of the war that German units were in ceaseless combat for four to six months without rest or refit (Heimdal Publications).

The most significant part of this reorganization and reduction was the

disbandment of the Officer Candidate Regiment. Since the bulk of this ad hoc

unit consisted of trained and experienced NCOs and soldiers whose battlefield

achievements had earned them admission to the Fahnenjunker der Infanterie Schule

in the first place, they were needed to populate combat divisions on other

fronts with their experience and leadership abilities. Both Operation Market

Garden earlier in September 1944 the secretive mustering of forces for the

Ardennes Offensive were the main reasons.

Simultaneous with the Germans’ deliberations, occurred what was intended to be a

surprise attack made by the US XII Corps (the other corps in Patton’s Third

Army) to outflank Metz to the distant north. It was successfully detected and

countered by General von Manteuffel’s 5. Panzer Armee, forcing now the entire

Third Army over to the defense. So far, the Germans were showing themselves

capable of mastering the circumstances – however adverse and tenuous they were. For von Knobelsdorf and 1. Armee, the extent of that successes to date now

brought them a two-week stalemate which in turn bought time to further

reorganize the defense of Metz.

During the stalemate phase, American activity in the Metz area of operations

continued in the way of small attacks and patrolling. However, the most

significant activity was an intensive XX Corps training program to develop and

instill techniques, tactics and procedures that would successfully reduce the

fortress’ defenses. Many were experimented with and tested during patrolling. These would prove to be valuable lessons, for the American command had decided

that the only way to take the fortress city was to successfully place a force in

its rear – to the east – and reduce the fortress east to west, fort by fort and

take the city block by block.

Illustration 7. American Infantry enters one of the Metz forts during the reduction process. The month long lull during much of the month of October was not a period of inactivity for either side. US Infantry units used the time to develop and train on tactics to successfully seize such fortifications. In some cases, the graduation exercise was an actual attack on such a fortification (Heimdal Publications).

Phase III:

United States forces achieved a tactical surprise when they initiated a new

offensive on 3 November 1944. While the Germans were fortunate to have directed

reinforcements to the exact spot the Americans directed their initial attack –

between the 19. Volksgrenadier Division and the 416. Volksgrenadier Division –

the defenders were nonetheless steadily reduced. The tactics developed over the

previous month paid off for the Americans and the outer defenses gradually fell

away. On 14 November a new German commander was appointed, Generalleutnant

Heinrich Kittel. Kittel was a defensive expert from the Eastern Front. Capable

and seasoned, he nonetheless had been given the impossible to achieve.

Accordingly, by 17 November, the XX Corps’ relentless attacks found them poised

to enter the city of Metz itself. As the defenses diminished to a series of

isolated battles at forts that could still hold out, ad hoc battle groups were

declared at each location. The troops that comprised these Kampfgruppen were a

mixed bag of defenders. General Kittel, isolated by the nature of the combat,

set up a headquarters in the Mundra Caserne on the Ile Chambiere, one of the

islands on which the city was formed. By 21 November, he was wounded and

captured by US soldiers in the basement of a tobacco factory that was being used

as an aide station. Asked to surrender his forces, he correctly refused, noting

that he had already relinquished command to Oberst von Stössel, who was fighting

elsewhere in the defenses, and thus he, Kittle, had no authority to act in such

a capacity. It would take another three weeks to subdue the remaining pockets

barricaded in the various forts.

Illustration 8. Kittel’s last headquarters. It was in the basement of a nearby building where Kittel was receiving medical care for his recent wounding that US Army forces found him. Having passed command prior to admitting himself for medical attention, Kittel would correctly refuse the American demand that he surrender Metz and all forces defending the city. The ferocity of battle is evident in the damage to his headquarters (Heimdal Publications).

By the time Metz was declared clear of German resistance, a new threat to the

Allied advance had materialized with a surprise winter offensive through the

Ardennes.

With the defenders of Metz killed, captured or dispersed to other units and

other fronts, and given that the war’s end was a mere 5 months away, it is no

wonder the Metz 1944 cuffband remains such an obscure award even at the time of

its institution.

Illustration 9 and 10. The final surrenders. The strain of the hard combat and surrender are evident on the face of Oberst Vogel as he surrenders Fort Plappeville, 7 December 1944. The NCO and city official to his rear likewise show their anxiety. The American officer’s indirect salute seems to indicate a degree of disgust. A few day later (right) aftera massive bombing, Fort Jean de Arc capitulated. Accepting the surrender is Brigadier General Hartness (Heimdal Publications).

AUTHORIZATION, ISSUE AND WEAR OF THE CUFFBAND

The Metz 1944 cuffband was authorized by an order dated 28 December 1944. Allied

operations in the city of Metz successfully ended shortly before this Führer

announcement. However, only the period from 27 August 1944 to 25 September 1944

qualify it as a combat decoration, as this was the extent of the existence of Kampfgruppe von Siegroth, which bore the brunt of the initial fighting that

successfully repulsed Third US Army in the early fall of 1944.

The order implicitly defined the Metz 1944 cufftitle as both an cuffband and an

cufftitle – that is, both an award and a traditions insignia – since it was

awarded as a combat decoration and subsequently issued as a traditions service

award to those who qualified.

As a Combat Award:

Any member of the Wehrmacht authorized to wear it as a combat award had to have

been either a member of Kampfgruppe von Siegroth or had to have operated

independently within the defensive sector assigned to Kampfgruppe von Siegroth. In both instances, a minimum of seven days in the specific defensive area was

required. However, if the individual was wounded or killed in action, regardless

of the minimum time served in the defensive area of Kampfgruppe von Siegroth,

the cuffband was authorized as a combat decoration.

Illustration 11. Generalmajor von Siegroth, under whose name the cuffband was officially awarded.

The cuffband was made available to all branches of the Wehrmacht, to include

officials, as well as to NSDAP members as long as the prerequisites were met. No

doubt this unusual step was due in part to the nature and variety of the forces

gathered together for the defense of Metz. It is probably as likely that the

extension to party members in particular was as much an effort to put an

honorable face on the wholesale abandonment of Metz by party members just prior

to the battle, as it was that any NSDAP member possibly might actually have

qualified for the award. Research to date has not uncovered an award to any

other than members of the Heer.

Application for the decoration was made through the company commander by means

of a proposal list. The list was to be in two copies and forwarded to the

General Inspector for the Army Leadership Schools for Infantry Officer Candidate

School VI (VI. Schule für Fahnenjunker der Infanterie). In the case of party

officials who might qualify, it can be assumed that such application would not

go to a military company commander, but straight from the appropriate party

branch to the General Inspector of Schools. Application for the award was

established for a period beginning 31 January 1945 and was to have been extended

only to 1 June 1945. All applications ceased for all intents and purposes on 8

May 1945, with the unconditional surrender of Germany. However, as with some

combat decorations, it is possible that awards of this cuffband continued for

several weeks after the surrender.

As a combat decoration, the number possibly eligible for the award probably did

not exceed 4,000 – i.e., the initial strength of the 462. Division - of which

only approximately 1,800 were officer candidates, and another 1,500 NCO

candidates. Within a month, all of these personnel were reassigned throughout

the Wehrmacht. The cuffband award was primarily meant for the officer

candidates. Next of kin were authorized to receive the award on behalf of the

deceased and one example of the award and one copy of the award document were to

be forwarded.

As a Traditions Award:

The Metz 1944 cufftitle was also designated a traditions award. It was

authorized in the same directive/order to all officers, noncommissioned

officers, officials, men (in essence all cadre and headquarters personnel) and

students of Infantry Officer Candidate School VI, Metz. This authorization was

only extended during the period of assignment. Once a member of the staff or

cadre was transferred, the cufftitle was to be removed. Upon graduation,

students as well were to remove the cufftitle. Presumably, it was turned in to

the supply organization within the school for later reissue.

Rarity of the Cuffband:

The Metz 1944 cufftitle must rank as amongst the rarest of combat awards of the

Third Reich. Consider a few of the significant factors attributing to this.

First, it was instituted with just over 120 days remaining in the war and was

thus, only in production and supply for a very short period of this time – and

almost certainly in only one form. Second, the units eligible were ad-hoc, in

some cases ill-defined, and existed for a period of roughly less than 90 days –

in the case of the Officer Candidate Regiment as a battle formation, less than

30 days. Tracking these recipients down and making and award – even a single

piece of the several a recipient was authorized – was a difficult proposition by

February 1945.

Additionally, School VI was relocated when combat operations forced the school’s

disbandment. It relocated to the city of Meseritz, which ended up in the Soviet

occupation zone/East Germany immediately after the end of the war. The exact

date of the relocation was not able to be determined, but even if it took place

once Metz was under siege in the early fall of 1944, the school could not have

lasted more than six or seven months until the end of the war. It is possible

the earliest the school was relocated coincided with the disbanding of the

Officer Candidate Regiment during the battle at the end of September 1944. It

seems more likely that it was relocated once Metz became untenable in late

November 1944. It is reasonable to think the school was functioning again in Meseritz by January-February 1945.

Considering the late December 1944 order instituting the cuffband, it is also

most probable that it was available for issue around February to March 1945. A

former member of the Metz school, in an excerpt from a letter dated 9 September

1957 stated that no awards were made before 21 January 1945. However, not enough

of the letter was available to research in order to determine the significance

of this date, but it may be indicative of when either the school was again

functioning in Meseritz, or it could indicate when awarding may have begun.

An officer course was roughly a six-week course, with some newly commissioned

officers going on to various specialty schools. T herefore, the number of Meseritz officer classes entitled to the cufftitle, probably numbered only three

or four before the end of the war. If one assumes about 1,500 candidates per

class and a cadre of a less than two hundred, roughly about 6,000 overall would

have been eligible and thus, the number available for issue might have been

between 6,000 and 30,000, given that multiple examples of cufftitles/campaign

awards were issued for an array of uniforms on which it was authorized to be

worn. But, there were probably fewer officer candidates made available in the

last three months of the war and the production run this late in the war –

regardless of the numbered ordered - was probably much less 30,000.

Only an extremely small set of individuals of the Waffen SS, NSDAP, Volksturm

and battlefield replacements of other Metz defenders - if in fact there was

anyone qualified at all from these “eligibles” – could possibly have ever

received the award. Thus, based on all of these constraints, facts and

assumptions, the overall production run of cuffbands/cufftitles had to have been

relatively small. As a guess, under normal conditions, the run might have been

only between 5,000-10,000 machine embroidered examples. Given the conditions

already mentioned, and its scarcity to collectors today, it seems probable

something on the order of 5,000 embroidered examples were ever produced and

submitted in to supply channels – fewer ever distributed – and much fewer

survived the last sixty years.

There is hardly any photographic evidence to even substantiate that it was

produced, issued and worn. However, two pictures in Gordon Williamson’s and

Thomas McGuirl’s book, German Military Cuffbands, 1784~Present, shows two of the

only known photographs substantiating that it in fact was. One, on page 59 shows Generalmajor von Siegroth in a Knights Cross presentation ceremony in March 1945

(von Siegroth was a colonel during the actual battle, so was promoted shortly

thereafter). The Ritterkreuzträger is Fahnenjunker Oberfeldwebel Willi Schmückle

and his award was made on 15 March 1945. Schmückle was assigned to 6. /

Fahnenjunker Regiment 1241 at the time of awarding. Generalmajor von Siegroth is

the only individual wearing the cuffband in the photo. He would obviously wear

it as a campaign award but at the time may have still been in charge of the

school. The second picture, on page 60, clearly shows an officer candidate in

what also clearly looks like a school training environment. The cufftitle is

mounted on his overcoat. The overcoat and the picture setting are evidence that

it was issued to students in the winter of 1945 at the relocated Schule VI für

Fahnenjunker der Infanterie.

Fewer than a half dozen authentic examples from collections were able to be

studied for this article. Each example observed conformed to the standard

presented here. There will be those that will argue out of want that

this-or-that variation is authentic – and thus, that many more examples in fact

exist. But, to date, no research can substantiate any such variation beyond

hypothesis, or deduction…and no strong case can be made for either given the

circumstances of the Metz 1944 cufftitle’s creation, institution and awarding.

Order of Battle:

There is no substitute for information concerning order of battle for the

serious campaign award collector. This has been emphasized in previous cuffband

articles. Knowledge of which units fought and who comprised their leadership is

invaluable toward establishing authenticity of not only award documents but also

of the less substantial stories that often amount to the provenance of an actual

award. The nature of the ad-hoc formation of many of the units defending Metz

and their continuous reorganization and changing leadership complicate the task

for establishing clear command relationships for study of the Metz 1944 cufftitle. It is additionally indicative of how the Germans, forced by manpower

shortages and setbacks on all fronts by this point in the war, drew on every

resource, no matter how ill-suited to the task. Uncharacteristically, the German

defenders were not thorough in keeping battle logs. Again, this was a function

of the conditions under which the Germans threw the defense together. To the

extent that records were kept – and now survive – they are far from complete. Nonetheless, some detail has been able to be reconstructed and is provided here.

Illustration 12. Sinnhuber.

Illustration 13. Standartenführer Kemper.

Oberbefehlshaber West

Generalfeldmarschall Model (also in command of Heeresgruppe B) – later, prior to

the start of the battle, Generalfeldmarschall von Rundstedt

Heeresgruppe B

Generalfeldmarschall Model (demoted back after giving the Commander in Chief

position to von Rundstedt.

Herresgruppe G

Generaloberst Blaskowitz

1.Armee

General der Kavallerie von der Chevallerie – later General der Infanterie von

Knobelsdorf. (In August 1944, prior to the start of the Metz battle, this army

was comprised of no more than 9 infantry battalions, 2 batteries of artillery,

10 tanks and an odd assortment of anti-tank and reconnaissance units, having

been badly decimated in the Allied breakout. However, the reinforcements Model

had pushed hard for when he was OB West, began to arrive just a couple weeks

ahead of the renewed Third US Army attack toward the Moselle River).

LXXXII Armeekorps

General der Artillerie Sinnhuber

XIII SS Panzerkorps (having the “Panzer” designation in name only and no Waffen

SS forces assigned to it at this point in time)

Generalleutnant Priess

Echelons below corps changed command relationships several times during the

battle. Thus, at various times, the SS Korps commanded Heer units and

visa-versa. They are listed here in numerical order.

3. Panzergrenadier Division (elements along the Mosselle River by 2 September

1944)

5. Panzergrenadier Division (elements along the Mosselle River by 2 September

1944)

17. Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division , "Götz von Berlichingen” (refitting in 1.

Armee area of operations)

19. Volksgrenadier Division

Oberst Karl Britzenhayer

416. Volksgrenadier Division

Generalleutnant Kurt Pflieger

462. Division (Initially only a garrison headquarters staff responsible for the

various schools and replacement units vicinity Metz).

Generalleutnant Walter Krause (designated also as Fortress Metz Commander on 2

September 1944).

Initially only a headquarters and staff, it was responsible for the various

schools, training and replacement operations as part of Wehrkreis XII in

Wiesbaden. Composed initially of about two infantry training battalions and

miscellaneous specialists, by 3 September it was able to form the equivalent of

three regiments, totaling about 14,000 men. As the battle plan developed, it

tended to bare the brunt of the command and control of all forces operating in

the immediate Metz defenses. For a period of time after 7 September, it fell

under the III SS Panzerkorps .

One regiment was formed by the Officer Candidate Regiment, Military District XII

– Oberst von Siegroth

One regiment was formed around the 1010. Sicherheits Regiment – this regiment

had retreated from France and was comprised mostly of weak, elderly and

convalescents - Oberst Richter

One regiment was formed out of the NCO School of Military District XII – Oberst

Wagner

1217. Division

Oberst Anton

Likewise, the echelons below divisions changed command relationships from time

to time. These commands were not initially fighting units, but training

organizations.

SS Nachrichten Schule, Metz. This unit was joined by two Heer replacement

battalions and fought on the east bank of the Moselle, south of Metz.

Standartenführer Ernst Kemper

SS Nachrichten Bataillon ,,Berg”

Ersatz und Ausbildungs Bataillon ,,Voss” (mostly elderly and infirm)

Fortress Machinegun Battalion

Fortress Infantry Battalion

Reicharbeitsdienst Bataillon

Volksturm

Illustration 14. The Metz 1944 Cuffband (Scott Pritchett collection) on the top and mint example of the cufftitle on the bottom(Courtesy Greg Domain Collection).

DESCRIPTION

The Metz 1944 cuffband is typical in both materials and construction style of a

number of different Heer cufftitles. As such, it is very similar to the standard Großdeutschland and Infantrie-Regiment List cufftitles, except in color

arrangement and lettering style. Thus, it generally follows the more prevalent

style of a thick wool band with embroidered title, bordered top and bottom by

silver-grey soutache/Russia Braid. It has a black base cloth background. One

source attributes the color selection to possibly reflect the traditional silver

and black colors of the city of Metz. Since all other Heer cuffband awards

exhibit a degree of heraldry or symbology in their motif, this seems likely as

the reason for these colors being used, as there is little if anything else in

the appearance of the Metz 1944 cuffband that illustrates traditions or symbols.

Illustration 15. A close up study of the embroidered numbers. Note the direction of the thread strokes on each number. This does not vary on any of the known originals inspected during the research of this article. (Frank Heukemes Collection).

OBVERSE

The band measures 34mm wide, with top and bottom 3mm wide soutache’ running its

length. The soutache’ should be machine stitched along its length and positioned

completely tangent to the edges of the base cloth. The thread used in the

machine stitching will be of a silver-white color. The Latin script title “Metz

1944” extend a length of approximately 12mm from lowest left foot of the “M” to

the right most tip of the cross arm extension on the last “4” across the center

of the length of the cuffband. The letters are embroidered in a silver-white

cotton thread. A key aspect of the embroidery of the letters/numbers is that the

stitching runs horizontally on vertical stokes and vertically on horizontal

strokes. There is usually a visible shade of color difference between the soutache’ color and the letter/number embroidery color, the latter being more

white. The ends of a full-length (about 44 cm) cuffband should have a vertical

white line of machine stitching about 3-5mm from the ends. This is typical of

full-length Heer cufftitles and cuffbands and served to delineate the length of

a complete band when cut from a roll or production length of cloth. It may also

provide some additional tacking to the ends of the soutache’.

Illustration 16. A close up study of the end of an original Metz 1944 cuffband. It clearly illustrates the vertical stitching that typically finishes the ends of a complete cufffband. It is possible that an original may not have these present as, when trimmed to fit around the sleeve of the variety of uniforms for which it was authorized, the length of the band could be trimmed ahead of application if the circumference of the sleeve was small. Additionally, originals bands removed from a uniform cuff post-war are often cut leaving the folded under ends sewn to the sleeve (Scott Pritchett collection).

REVERSE

The backside of the letter embroidery is a mirror image of the front. One of the

only differences can be the underside stitching thread from the machine bobbin

that secures the top stitching in place. This will frequently show through

between the top embroidery thread in a yellowish color. Another difference is

that the thread slack that makes the embroidery of the letters able to be done

continuously without finishing each letter, stopping the machine, cutting the

thread and restarting the next letter will be seen running between the

letters/numbers. This single thread indicates where the formation of the letters

and numbers started and finished. For example, on the “4”s the last stroke to

finish off the number appears to always be the cross arm. The embroidery

typically starts at the back of this part of the number and finishes at the

forward point, then jumps to the next number at the back end. This small detail

is something that would not vary on a production run made off the same series of

embroidery machines, but could vary based on the type machine model used.

Illustration 17. The reverse of the letters/numbers embroidery. It is almost a mirror image of the obverse. Note the connecting threads between the letters ad numbers that are indicative of how the embroidering needle skipped from figure to figure. Also note the white basting thread along the bottom turn up edge. This thread may or may not be present on an original cuffband today, depending on its wear and tear over the past sixty years, since the thread is so loosely applied (Scott Pritchett collection).

The silver-white stitching that secures the soutache’ to the edges of the cuffband mentioned above, shows through on the reverse in straight machine stitching about 1.5mm in from the edges. The folded over portion of the base cloth typically doubles over on to the back, extending about 1 cm or more, both top and bottom, inward toward the centerline of the reverse. As well, the vertical machine stitching along the ends will usually show if the cufftitle is in full length.

Illustration 18. A close view of the backside embroidery that clearly

illustrates how well it is executed on an original band. Note that on this

example little of the basting thread sometimes present on the turn up remains.

The nature of the red substance/stain on the embroidery is not determined

(courtesy Frank Heukemes collection). Below is an additional close up of

the reverse of a mint cufftitle. While the folded over portions of the band

material are deeper than the previous example, this is an original cuffband. The

basting thread is pristine, both top and bottom as would be expected on a mint, unissued example (Courtesy Greg Domain Collection). Lastly is the reverse end of

yet a third example which illustrate the vertical finishing stitching found on

full length examples (Scott Pritchett Collection).

Illustration 19. A similar close up of the reverse embroidery of the numbers (Frank Heukemes Collection).

AWARD DOCUMENTS

As with all military awards made, an award document, or Bestizzeugnis,

accompanied The Metz 1944 cuffband. Completed award documents are excessively

rare to non-existant. However, two incomplete example styles have been pictured

in articles and references. Again, relying on Gordon Williamson’s and Thomas McGuirl’s work, these two styles are pictured on page 61. The first type is

merely the official template, which in fact could have been used in its exact

format. However, award documents were most frequently printed professionally in

variations. These were directed and approved by a headquarters. That

headquarters could be about any level, depending on what level of commander

could approve the award, but usually divisions and above. These templates were

found in published regulations. Therefore, accompanying all Verodnungsblatt

(regulations) setting forth official awards was a generic format example of how

the award document would be set up and worded.

The guidance set out in the Heeres Verordnungsblatt of 1944 was as follows:

Bestitzzeugnis

In Namen des Führers

wurde dem (Dienstgrad) (prompt for rank)

(Vor und Familienname) (prompt for full name)

(Truppenteil) (prompt for unit)

das ärmellband ,,Metz 1944” verliehen

(Ort und Datum)

(prompt for location of issuance)

(Dienststempel)

(prompt for official unit seal)

von Siegroth

Generalmajor

The cuffband was to be issued in all cases under von Siegroth’s signature, so

all printed versions were to reflect his signature block. The format for this

document was DIN A 5.

A second known example was a more ornate variation of the regulation template,

featuring a German fracture type font throughout. The information was identical

to the template, but styled differently. This variation was also published in an

article some 15 years ago by Herr Andre Hüsken. It is shown here again.

Illustration 20. An ornate version of the Metz award document. The regulation specified DIN A 4 size. It can be assumed with some degree of confidence that this version may have been intended as the official printed version as translated from the regulation. The filled in rank, unit, location and presentation date, along with von Siegroth’s signature (facsimilie?) are all indicative of an intent to present this document in February 1945. As stated above, February 1945 may have been the earliest date where awards were rendered (Illustration courtesy Toby Rowan).

Likewise, an appropriate entry should have been made in the Soldbuch and Wehrpass of each recipient. It is possible that the Soldbuch for officer candidates attending Schule VI für Fahnenjunker der Infanterie could also have had an entry reflecting the issue of the school uniform accouterment on page 22. Research in the form of veteran written recollections indicate that such entries were made. However, locating actual entries, like locating examples of the award document, seems unlikely and none turned up by this research effort.

WEAR

Research does show that campaign awards (including campaign shields) could be issued to awardees in multiples, sometimes up to five. This practice would account for the authorized display on different uniforms. By regulation, the Metz 1944 cufftitle was authorized for wear on the left arm of the Waffenrock (parade dress), the Mantel (overcoat), the service and field service uniforms. Because by regulation the award was authorized by qualified party members, it was also authorized on party organization uniforms. It was positioned 12-15 cm above the lower edge of the uniform cuff or 1 – 1.5 cm above the top edge of the turn back French cuff.

REPRODUCTIONS

The Metz 1944 cuffband has been reproduced for decades. There are probably many

more fakes available than originals. However, because originals are so rare,

fakes are seldom convincing. Two of the most common errors are constructing the

cuffband in the completely wrong materials or in the wrong styles. For example,

a cuffband that is constructed in BeVo, flat wire embroidery, or RZM style would

be completely wrong. Another common error of the worst fakes is the incorrect

formation of the letters and numbers. For example, a common fake that surfaces

frequently has open number “4”s versus the correct closed-pointed “4”. Some

fakes combine many of these errors together. Pictured below are two post-war

examples that illustrate these points well.

Illustration 21. Post-war flat wire embroidered reproduction (top) and an example (bottom) of a fake that is machine woven, even in the replication of the Russia braid. Note that besides the construction styles being incorrect, that the lettering and numbering is wrong as well (Courtesy Peter Wiking).

Illustration22. A variation of the top example from the previous illustration. The main difference between the two is the styling of the letters and numbers. This is another example from a private collection that does not conform at all to the accepted standard. It may in fact be a post war reproduction. It is done in the flatwire embroidery more commonly associated with SS/SA cufftitles. While the owner/collector believes it to be an authentic wartime example, it could be that this variation was made specifically for the SS and NSDAP. However, this notion is pure speculation. Given that the regulation authorized qualified members of such organizations to receive the award, perhaps such a style was made or prototyped for such an intended purpose. However, as noted earlier, no evidence of such awards actually being made has surfaced. It is most likely this version is yet another post-war fabrication (Courtesy Peter Wiking).

Illustration 23. The reverse of the flatwire embroidered example (Courtesy Peter Wiking).

Illustration 24. Detailed view of the flatwire embroidery of the letters. Note the seven rows o wire that forms the cuffband borders (Courtesy Peter Wiking).

Illustration 25. Detail of the flatwire embroidery of the numbers (Courtesy Peter Wiking).

Illustration 26. Magnified view of the end of the flatwire embroidered cuffband (Courtesy Peter Wiking).

Illustration 27. A BeVo style Metz cuffband believed to be a reproduction. Although well made in general by capturing the BeVo style, it lacks the defined “salt and pepper” reverse of a genuine SS BeVo manufactured cufftitle. It is reminiscent of those reproductions that appeared as early as the 1970s on the collector’s market.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As always, several people came forward to share their

collections and knowledge to assist the research of this article. Frank Heukemes

and Peter Wiking in particular are owed much thanks for providing pictures of

examples from their collections. As always, Jacques Calero found pictures

pertinent to the subject. While unable to contact him through Heimdal

Publishers, Mr. Frank Kemp’s two books on the battle for Metz, published over

the span of two decades with in depth research from the French and US Archives,

as well as US Army divisional veterans organizations proved invaluable sources

for the history of the battle. Heimdal Publishers, themselves did not respond

either, but their historical series on many units and battles of WWII are

exceptional works of research. Ade Stevenson was kind enough to share an example

of the Götz von Berlichingen cufftitle from his collection that greatly added to

the visual presentation within the article. Toby Rowan provided invaluable

research documentation directly drawn from wartime regulations that contained

much of the technical information on the cuffband. Greg Domain’s pristine

original example added to the visual information immeasurably. Lastly, late in

the development of the article, “Grenadierkarl” from our Forum allowed the

illustrating of the last example of a reproduction. Thanks to all.

![]()

© Copyright Wehrmacht-Awards.com LLC |